|

| Home | What's New? | Cephalopod Species | Cephalopod Articles | Lessons | Bookstore | Resources | About TCP | FAQs |

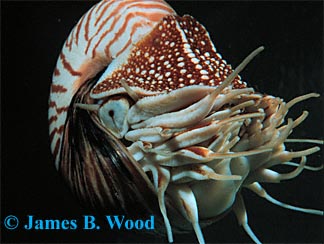

What We Don't Know About Nautilus<< Cephalopod Articles | By Dr. James B. WoodOnce, the ocean was full of externally-shelled cephalopods. Two subclasses, the Nautiloidea (late Cambrian to present) and Ammonoidea (Devonian to Cretaceous) were commonly found in the world's oceans and ranged greatly in size and morphology. Today, all of the Ammonoidea are extinct. There are only two genera (Allonautilus, Nautilus) with a total of seven species of nautilus left.  No one has been able to track a nautilus in the wild from hatch to maturity. In fact, no one knows where their eggs are laid in the wild. Captive nautiluses often develop buoyancy and shell formation problems. Only three places have been able to produce fertile nautilus eggs in captivity and no one has been able to raise one to maturity. We do not know what the life span is or how long it takes a nautilus to reach maturity. We do know that these ancient mollusks drive in the slow lane, especially when compared to their modern cephalopod relatives. Most cephalopods live for about a year and die. Some, like Idiosepius pygmaeus are born, grow, reproduce and die is 80 days or less. Even the giant octopus, Enteroctopus dofleini, only lives for about three years. Deep-sea octopuses like Bathypolypus arcticus may live longer. Since they are exothermic and they live at 4°C their metabolism is extremely slow. Still, most cephalopods studied to date live for about a year. Nautilus may live for 20 years. Cephalopods tend towards semelparity, the life-history pattern of reproducing once and dying. Entire populations of some species exist only as eggs at certain times of the year. At times there are no adults or juveniles, just eggs. And all of them are in one basket. This strategy is the opposite of the bet-hedging strategy that many animals do to ameliorate the effects of environmental and ecological change. For most cephalopods, the population can rise like a phoenix from seemingly nothing during favorable conditions. In bad times there are few and fisheries based on them rapidly collapse. Nautilus is an exception to the general cephalopod pattern here too; these living fossils reproduce for many years although, you guessed it, no one knows how long. Cephalopods typically produce hundreds to half a million eggs depending on species. Most of their hatchlings become food for something else. The potential is there for huge population booms when there are in good times. Again, nautilus is different. Once mature, nautilus only lays a few eggs each year, about 12. These eggs are huge and are among the biggest eggs relative adult size of any animal. The nautilus shell is beautiful and is prized by shell collectors. To a lesser degree these animals are collected for the aquarium trade. The ancient Greeks described the logarithmic spiral as "The Golden Rectangle." The ever-increasing spiral is used as a logo for many businesses as a symbol of both mathematical and aesthetic perfection. Nautiluses are collected by traps in parts of the world where people have to worry about their next meal even more than a graduate student. I'm not aware of any restrictions on the collecting of nautilus, but even if there were some, enforcement would be difficult. Nautilus grows slowly, takes a relatively long time to reach maturity and they lay only a few eggs. While we don't know how long they take to reach maturity, how many are out there or how many are collected from the wild, we do know that slow growth rates, a long time till maturity and low fecundity are life-history traits of an animal that will not bounce back quickly if they are over-exploited. There are many "what if's?" and unknowns about nautilus. I'm unsure if they should be protected, as there is little data. If they should, will we have sufficient data to make a strong argument based on facts of population size and impact of fishing? Even then, how would we be able to enforce regulations in developing parts of the world? There is so much we don't know about nautilus, we need to learn much more.

| ||||||

| Home | What's New? | Cephalopod Species | Cephalopod Articles | Lessons | Resources | About TCP | FAQs | Site Map | |

|

The Cephalopod Page (TCP), © Copyright 1995-2024, was created and is maintained by Dr. James B. Wood, Associate Director of the Waikiki Aquarium which is part of the University of Hawaii. Please see the FAQs page for cephalopod questions, Marine Invertebrates of Bermuda for information on other invertebrates, and MarineBio.org and the Census of Marine Life for general information on marine biology. |