Octopus vulgaris, the Common octopus

<< Cephalopod Species

Octopus vulgaris, the Common Octopus, is found world wide in tropical and semitropical waters from near shore shallows to as deep as 200 m. In actuality, most scientiststs believe that O. vulgaris actually contains a number of related sister species.

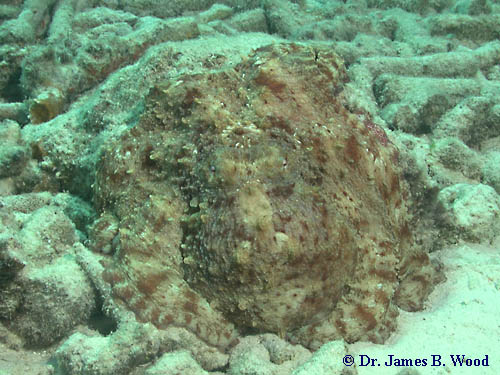

We never would have seen this large Octopus vulgaris if it hadn't moved. |

However, taxonomists have not yet decided how to split the species. Until they do, I'll refer to them all as O. vulgaris. Another common identity problem with the common octopus, is that in many commercial industries, such as the food and aquarium trade, they list all species of octopuses as O. vulgaris.

Despite these identify issues, the O. vulgaris is commercially important and accounts for a large percentage of octopus fisheries. From 20,000 to 100,000 metric tons are landed yearly. They are commonly collected in octopus pots. These were traditionally made of clay but in modern times they are typically made of plastic or PVC. Octopuses pots are not baited like crab and lobster traps, rather, they provide a seeming safe home. In addition to being commercially important, this species is also one of the most commonly studied cephalopods.

Octopus vulgaris lives for 12 to 18 months. After they hatch from on of 100,000 to 500,000 carefully guarded rice grain sized eggs, they spend 45 to 60 days in the plankton. During this time, most of them become food for something else. Those that survive settle out and begin a benthic (bottom dweling) life. Dr. Roger Villanueva as well as several Japenese workers are amoung the few people who have ever reared these small egged octopuses to settlement.

While swiming over the reef in Boanire, I first spotted the flame scallop shells and other middens. A quick dive down and I found this Octopus vulgaris |

O. vulgaris is occasionally active during the day. Dr. Mather reports that they are out hunting during the day 12% of the time in Bermuda. In Cephalopod Behaviour, Hanlon and Messenger (1996) theorize that cephalopods that live in complex environments are especially good at camouflage and have a large repttwar of patterns. O. vulgaris certainly fits this description as they can be incredibly good at matching their surroundings. Finding them can be difficult.Some species of octopuses, like Octopus vulgaris, leave piles of shell and crab carapaces outside their lairs. These discards are called midden and are useful to divers and scientists for several reasons. O. vulgaris are masters of camouflage (Click here for a video clip of O. vulgaris camouflage) and it is often easier to search for them by searching for midden piles than looking for the animals themselves. While swimming above a reef numerous clean shells can catch my attention from a distance of 5 meters or more, I'm unlikely to see a camouflaged octopus at half of that range unless it moves. Once you find a midden pile the next step is to dice down and look for a lair. O. vulgaris lairs are typically holes in rocks or excavated under or between rocks. If the octopus is home, you are in luck. If not, a careful look in the surrounding area may find him as he is likely out hunting. If you still have no luck, your chances are good if you take another look a few hours to a day later.

Scientists are interested in midden piles for two reasons. One is that the discarded shells give us a very good idea of what the octopus eats. Another is that the middens give us a different view of what animals are in the area. For example, in Bonaire O. vulgaris was finding and eating a number of mollusks that we never could find ourselves. One of these was a rather large surf clam that the octopuses can obviously find. If it were not for octopuses conveniently laving middens for us, we would not have been able to add surf clams and others species to our Mollusks of Bonaire list.

|