|

| Home | What's New? | Cephalopod Species | Cephalopod Articles | Lessons | Bookstore | Resources | About TCP | FAQs |

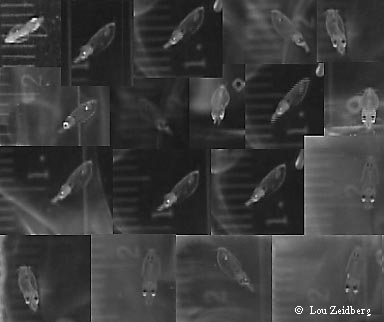

Loligo opalescens, California Market squid<< Cephalopod Species | By , Monterey Bay Aquarium Research InstituteLoligo opalescens is a small squid (mantle length ML up to 160 mm) in the family Loliginidae. It is a Myopsid squid, and that means that they have corneas over their eyes. The species lives in the Eastern Pacific Ocean from Baja Mexico to Alaska, USA. They live within 200 miles of shore. The life cycle of L. opalescens has four stages, eggs, hatchlings (called paralarvae), juveniles, and adults. These squid live for 4-9 months.  Loligo opalescens eggs are laid on sandy bottom substrates in 10-50 m depth, although there is a report of a shrimp trawler pulling up eggs from 800 m. Females encapsulate hundreds of eggs in a sheath that is made of many layers of protein. Bacteria grow between the layers and may serve as an antibiotic to prevent fungal infection. Females insert the egg capsules into the sand with a sticky substance that anchors them in place so that the ocean surge can aerate them. The presence of eggs on the bottom of tanks stimulates females to lay more eggs. Groups of capsules are placed in masses that can extend into egg beds. Some egg beds can cover acres of the ocean floor. The eggs take 3-5 weeks to hatch. The warmer the water, the shorter the incubation time. Bat stars, Asterina miniatus, are the most prevalent predators of eggs. Fish do not eat them, although they will nip at eggs not covered by the sheath. There is no brooding or parental care.  Paralarvae of Loligo opalescens hatch from the eggs and immediately begin swimming, where they go is unknown, but Loligo pealei swim to the surface in the first 12 hours post-hatching. Paralarvae must rapidly learn to hunt, as their yolk only lasts a few days and some lose their yolk upon escaping from the egg sheath. Through a series of trial and error these 2-3 mm ML hatchlings learn to eat copepods and other plankton in the first months of their lives. They are found in the greatest abundance at 15 m depth by night and 30 m depth by day. Thus, they perform a daily vertical migration of 15 meters, no small feat when you are only 3 mm long. This daily migration coupled with the shear zone created by tidal and near-shore currents cause the hatchlings to become entrained within 3 kilometers of shore. That is good for them because in the near-shore environment the plankton is smaller and easier for them to eat.  By the time Loligo opalescens reaches 15 mm mantle length (about 2 months old) they are strong enough to swim in shoals. These juveniles form groups of tens of individuals and swim over the shelf in search of food. Those that have survived to this point can hunt with the tentacular strike as seen in the adults. At some point between 4-8 months their sexual organs mature and they are now considered adults. Sexually mature animals can be 70-160 mm ML and weigh about 40 grams. Adult Loligo opalescens move off the continental shelf by day and can be found to depths of 500 m. Adult shoals return to the surface at night to hunt. At some point these shoals move on shore to spawn where aggregations can reach million of individuals. Originally it was thought that the adults died after spawning, as the egg beds were often littered with dead squid. Now there is debate as to how long adults live after their first egg deposition and whether they can spawn repeatedly over the last weeks or months of their lives. The fishery for Loligo opalescens began with the Chinese in Monterey Bay, California in 1860. By the turn of the century Italian fishermen had assumed the leading role. After WWII there was resurgence in squid fishing. Since 1981 the fishery has really grown, as effort in Southern California has increased. Now Southern California, mostly areas around the Channel Islands, comprises 90% of the squid landings. The fishery in Monterey Bay occurs from April to November coinciding with the upwelling season. In Southern California landings begin in November and continue through April correlated with the greater mixing of winter storms. Since 1993 squid has been the #1 fishery in California with landings of 118,000 tons and $41 million in 2000. The population fluctuates greatly with the El Niño. During these warm water, nutrient poor years landings can disappear entirely in certain areas. For more information on these squid, see: Calamari on camera—sizing market squid by video. This is some of Lou Zeidberg's Ph.D. work. Thanks for sharing your work Lou!

| ||||||

| Home | What's New? | Cephalopod Species | Cephalopod Articles | Lessons | Resources | About TCP | FAQs | Site Map | |

|

The Cephalopod Page (TCP), © Copyright 1995-2024, was created and is maintained by Dr. James B. Wood, Associate Director of the Waikiki Aquarium which is part of the University of Hawaii. Please see the FAQs page for cephalopod questions, Marine Invertebrates of Bermuda for information on other invertebrates, and MarineBio.org and the Census of Marine Life for general information on marine biology. |